Access to care for type 1 diabetes (T1D) is a fundamental human right like water. Yet, millions worldwide in low-resource setting still struggle due to late diagnoses, limited insulin availability, high costs, and inadequate healthcare infrastructure. Overcoming these challenges requires global collaboration, innovative solutions, and strong research networks.

In February, we partnered with the World Diabetes Foundation, the University of Geneva Faculty of Medicine, and the East African Diabetes Study Group to host an international meeting in Copenhagen. Titled Type 1 Diabetes – Advancing a Global Road Map for Improved and Integrated Care in Low-Resource Settings, the event brought together 143 policymakers, experts, and researchers from around the world.

The event led to the 2025 Copenhagen Call to Action, a commitment to scaling up efforts ahead of the UN General Assembly’s 4th High-Level Meeting on Non-Communicable Diseases in September.

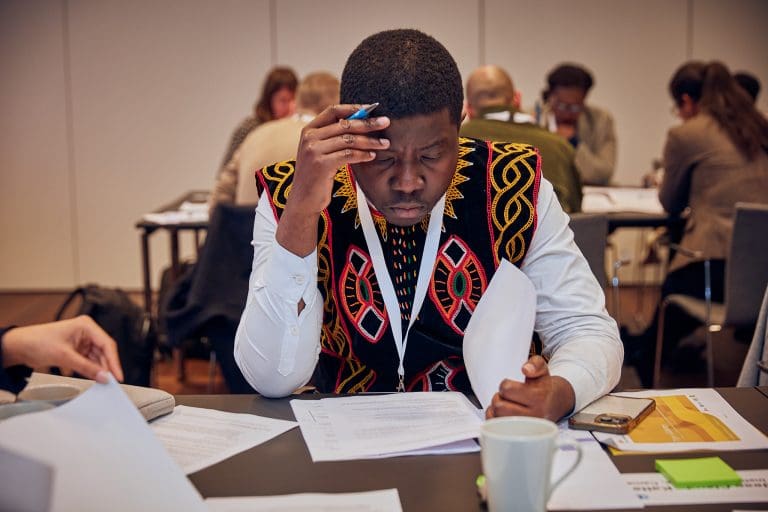

A key part of the meeting was a dedicated workshop for early-career researchers, designed to foster collaboration, share insights, and strengthen research capacity in T1D care. We spoke with three early-career researchers to hear their first-hand experiences and perspectives on the international meeting. 👇🏾

Home country: Cameroun

Research areas: Young-onset diabetes, Type 1 diabetes in African populations

I was invited as an expert on diabetes in Africa and peer-to-peer mentorship of early-career researchers to help shape the agenda for the early-career researcher programme. Recognising the value of continuous learning and networking, I saw this as an opportunity to engage with fellow researchers and experts in diabetes care.

My area of focus is researching diabetes manifestations in sub-Saharan Africa, where improving diabetes management in resource-limited settings is a pressing issue. The meeting provided a platform to exchange ideas, explore new research directions, and gain insights that could strengthen my work.

One of the most important insights was the role of the WHO Global Diabetes Compact (GDC) in addressing type 1 diabetes care challenges. Before the meeting, I knew little about its framework. Through presentations and discussions, I learned how the GDC helps governments and healthcare stakeholders develop sustainable solutions.

Launched in 2021, the WHO Global Diabetes Compact (GDC) aims to improve diabetes prevention and care worldwide, with a focus on access to affordable treatment and essential medicines. It supports governments in strengthening healthcare systems and ensuring better diabetes management.

📌 Key Goal: Make diabetes care more accessible and sustainable globally.

📌 Relevance: In 2024, 47 African countries adopted the GDC framework to improve type 1 diabetes care.

🔗 Learn more: WHO Global Diabetes Compact

The adoption of this framework by the WHO African Region in 2024—covering 47 countries—shows a growing commitment to systemic improvements. This highlights the need for researchers to align their work with global health initiatives to drive meaningful change.

The biggest challenges include sustainability of care programmes and the lack of comprehensive data collection systems. Sustainable care requires full integration into Universal Health Coverage — a system where essential healthcare, including insulin and glucose monitoring, is accessible to all, regardless of income.

Researchers can contribute by developing evidence-based care models tailored to local contexts, engaging policymakers, and advocating for long-term solutions. Establishing diabetes registries is also crucial for tracking disease trends, improving resource allocation, and strengthening public health strategies. High-quality data enables better healthcare planning and decision-making.

The HIV/AIDS research in Africa has been a successful model in driving transformational research that has led to improved outcomes for people living with HIV/AIDS.

The meeting expanded my network, introducing me to researchers, clinicians, and funding organisations working to improve type 1 diabetes care. I connected with institutions across different regions, and we continue discussions on potential joint projects.

Early-career researchers also remain connected through a dedicated platform on Slack that facilitates knowledge exchange, mentorship, and collaboration. These partnerships will help drive multidisciplinary approaches and support the scaling of interventions that can be adapted to different healthcare settings.

One of the most inspiring moments was meeting Micaela Villanueva, a medical student and research assistant from Peru. Despite being early in her career, her dedication to diabetes research stood out. She shared how mentorship from her supervisors in Peru shaped her skills and fuelled her passion for the field.

Her story reinforced the importance of mentorship in developing the next generation of researchers. Supporting young scientists is essential for advancing diabetes research and improving care globally.

With increasing national and global focus on improving diabetes care, I believe our research will help shape policies that enhance treatment in low-resource settings. By generating data-driven insights and advocating for sustainable healthcare models, we can influence decision-makers to prioritise type 1 diabetes within broader health agendas.

The discussions at this meeting reinforced the urgency of systemic improvements. I am optimistic that researchers, clinicians, and policymakers working together can drive meaningful progress, both locally and globally.

Home country: Peru

Research areas: Global health, non-communicable diseases, health systems, and food systems.

This meeting was a call to action. I have been working to improve insulin access in Peru, Kyrgyzstan, Tanzania, and Mali as part of a broader project called ACCISS. While I do not work directly in all these countries, we exchange experiences and learn from each other. Seeing how research is conducted in different settings helps identify both common barriers and unique challenges.

The main challenges are similar across countries: limited access to affordable supplies, poor availability in rural areas, and inadequate patient education. However, insulin procurement varies—some nations depend on donations, while others use centralised or mixed purchasing systems.

As an early-career researcher, I do not want to just describe these problems—I want to help solve them. This programme allowed me to connect with like-minded individuals who share the drive to turn research into real change.

Experiencing the inequities of the healthcare system and witnessing how people without financial resources can die from treatable diseases changed me forever.

During my hospital internship at Hospital Nacional Dos de Mayo in Lima, Peru, I saw firsthand the suffering of many patients, but what impacted me the most were the children with T1D. Their burden was not just the disease itself, but the heartbreaking reality that their survival depended on a life-saving medication they couldn’t always access.

I saw the fear in their eyes, the desperation of their parents, and the crushing weight of a financial burden that dictated their future. Watching them face an unfair battle broke my heart, but it also inspired me to fight for them, and with them, so that no child is left without the care they need.

One powerful takeaway is that achieving 100% insulin availability and affordability is not an unrealistic dream—it is a goal we must reach. The fact that it is difficult does not make it impossible. Just as access to HIV treatment once seemed unthinkable, the right policies, funding, and strategies can drive major progress.

Reaching this goal will take time, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where healthcare infrastructure, supply chains, and financial constraints vary widely. Setting a precise timeline is challenging, but even a 1% increase in insulin availability per year means lives are being saved. Each country must set realistic, sustainable targets, but the ultimate aim must remain 100% access.

Another key takeaway is the need to break silos within healthcare systems. Real change will not happen if researchers, healthcare workers, policymakers, and patient communities work in isolation. Collaboration is the only way forward.

The biggest challenge is survival. It sounds harsh, but that is the reality. In Peru, people with type 1 diabetes face insulin shortages, a lack of education on self-management, and unaffordable treatment costs. Without government support, managing the disease is nearly impossible.

As researchers, our responsibility goes beyond publishing studies. We must ensure our work leads to real action. This means collaborating with patient communities, amplifying their voices, and translating research into sustainable, evidence-based policies.

A strong example is the COHESION study by Professor David Beran and Research Associate Maria Lazo-Porras, which develops co-created interventions in Mozambique, Nepal, and Peru to improve diabetes care. The study operates at three levels—policy, health systems, and community—to design and assess feasible, sustainable, and scalable solutions. By working directly with communities, COHESION ensures that scientific evidence leads to meaningful policy changes and public health interventions.

Absolutely. This meeting was not just about exchanging ideas—it was about building alliances. I connected with researchers from different continents who, despite being miles apart, face similar struggles. Seeing their resilience and innovative approaches gave me new perspectives on how to conduct research with real impact.

I also met global leaders who have been working on these issues for years. Their insights reinforced my commitment to pushing for research that drives tangible improvements in diabetes care.

During the workshop, we developed episode manuscripts for the upcoming podcast show, DDEA Global Health Podcast on Type 1 Diabetes – Actions and Challenges. Four of the episodes were co-hosted by early-career researchers, including myself, alongside Gretchen Repasky, DDEA’s Education and Networking Manager.

One of the most inspiring moments for me was preparing and recording the episode “The Lifeline of Insulin and Technology”, where I co-hosted with Gretchen and DDEA Managing Director, Tore Christiansen. We interviewed Molly Lepeska, Project Manager at the ACCISS project (Health Action International, Peru). I already work closely with Molly and know just how much knowledge and experience she brings – so being part of this conversation was both a professional highlight and a great learning opportunity.

I also contributed to the Spanish-language version of the podcast, this time as the interviewee. I joined host Jose Omar Silverman Retana, postdoctoral researcher at Steno Diabetes Center Aarhus, and co-host Juan Pablo Pérez Bedoya, PhD student at the University of Antioquia. Discussing diabetes from the perspective of an early-career researcher was just as powerful.

What surprised me the most was the structure of the workshops. We were not passive participants—we were trained to engage in high-level discussions, challenge leaders, and contribute meaningfully. Sitting at the same table as influential figures from major organisations, and having them genuinely listen to early-career researchers like me, was incredibly empowering.

Research should not stop at identifying problems—it should drive real change. I see my work as a bridge between knowledge and action, developing innovative, sustainable solutions for diabetes care.

By integrating diverse perspectives and engaging key stakeholders, I aim to help create a more equitable and responsive healthcare system for people living with type 1 diabetes—both in Peru and globally.

This programme did not just give me knowledge and connections—it gave me confidence. It reminded me that my voice matters and that real change starts with all of us taking action. More than ever, I am ready to push forward, challenge systems, and contribute to a global movement that ensures no one is left behind in diabetes care.

Home country: India

Research areas: Diabetes education for resource-constrained settings

Attending the international meeting, Type 1 Diabetes – Advancing a Global Road Map for Improved and Integrated Care in Low-Resource Settings, and early-career researcher workshop was an invaluable opportunity to explore different approaches to managing type 1 diabetes (T1D) worldwide. I was especially interested in learning about strategies that could be adapted to low-resource settings like India.

One of the biggest takeaways for me was realising that the challenges we face in India—such as supply shortages and resource constraints—are not unique. Many low and middle income countries (LMICs) experience the same struggles. That’s why global discussions like the ones initiated at this international meeting are so important. They help us find shared solutions and build stronger collaborations, and are the way forward.

One of the biggest challenges is the lack of reliable data. We need real-world numbers on the financial burden of T1D, the availability and lack of supplies, and long-term outcomes of people with T1D. Without this data, it’s difficult to advocate for better policies or develop targeted interventions. Early-career researchers can play a crucial role by gathering and analysing this information, especially through international collaboration.

The meeting gave me the chance to connect with like-minded researchers who are just as passionate about improving T1D management. These discussions have sparked new ideas, and I look forward to working on joint projects that can make a real difference across countries.

Meeting global pioneers like Dr. Graham Ogle (paediatric endocrinologist working for Diabetes Australia as General Manager for the Life for a Child Program, and Adjunct Professor at the University of Sidney), and Dr. Catherine De Beaufort (paediatric endocrinologist and Associate Professor at the University of Luxembourg), and many others was truly inspiring—it was a dream come true! Hearing about their groundbreaking work and their dedication to improving T1D care was incredibly motivating.

My study on the financial burden of T1D among children in our clinic at PGIMER, Chandigarh, India, was what led to my selection for this programme. This experience reinforced my belief that our research is making an impact, both nationally and globally. The biggest lesson I took home is that collaboration is key—we can achieve much more when we work together rather than in silos.

I hope this event marks the beginning of long-term collaborative efforts in T1D research. Leaders like DDEA Managing Director, Tore Christiansen, and Bent Lautrup-Nielsen, Head of Global Advocacy at the World Diabetes Foundation, have done an incredible job in bringing us together, and I’m truly grateful for their work. A huge thanks to them and their team for organising such a meaningful programme.

EAN: 5798 0022 30642

Reference: 1025 0006

CVR: 29 19 09 09